Infection models will improve exponentially as public databases amass more variables.

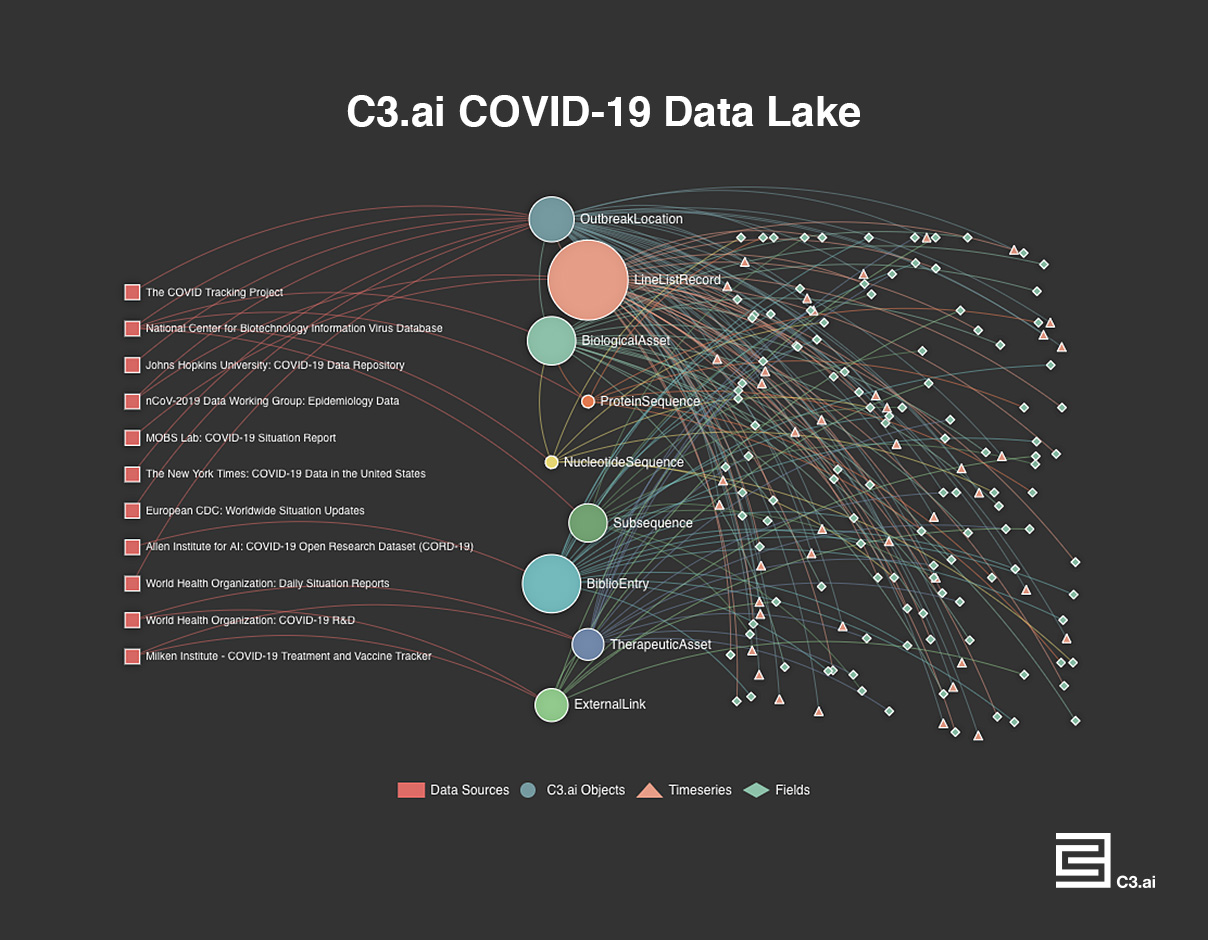

The C3.ai Covid-19 data lake.

The value of a network rises in proportion to the square of the number of users, observed Ethernet inventor Robert Metcalfe. Metcalfe’s Law— precisely expressed by the formula n(n-1)/2—is what enabled Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and all social networks. The more the merrier. But it’s exactly the opposite for pandemics. You’re safest on your own or in small groups. The harm goes up in proportion to the square of the number of your contacts.

Or rather it does until it doesn’t, according to 19th-century British epidemiologist William Farr. He didn’t guess. In 1840 he studied data from the 1837-39 smallpox epidemic and noted that the number of deaths followed a normal bell-curve distribution. Known as Farr’s Law, it’s his curves that we’ve flattened. As the journalist Michael Fumento said of Covid-19, “Communicable diseases nab the ‘low-hanging fruit’ first (in this case the elderly with comorbid conditions), but then find subsequent fruit harder and harder to reach.” That echoes Farr’s observation that pandemics burn out as fast as they start. Yet that tendency, and the data that back it, has barely been mentioned during the Covid crisis.

Farr obviously didn’t plot his data on a MacBook. The first useful, programmable and electronic digital computer, Colossus, was created by Alan Turing and friends a century later in England to decrypt the Nazis’ Enigma and Lorenz code-machine communications. After the war the British were so nervous that Colossus would end up in the hands of Soviet spies that they destroyed all plans and copies. A colossal mistake.

In the U.S., by contrast, the Eniac computer, designed to help create artillery tables, wasn’t turned on until November 1945, completely missing the war. Rather than destroy it or keep it secret, on Feb. 14, 1946, the War Department miraculously put out a press release with details and invited interested parties to meetings to share ideas. Yes, share! That simple press release is why technology is dominated by U.S. firms and Silicon Valley emerged in displaced California orchards and not in, say, Shropshire, England. Call it the Eniac law: Open is better than closed. Dissemination is better than secrets. Turns out, to invoke Metcalfe’s law, ideas network too.

Fast-forward to the Covid era, with apocalyptic pandemic models driving policy. A few short weeks after the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic, Silicon Valley veteran Tom Siebel’s artificial intelligence company C3.ai went live with an open cloud-based repository. Known as a data lake, it contains location and confirmed case data from the World Health Organization and Johns Hopkins, genome sequences of Covid-19 samples from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Virus Database, global patient data such as symptoms and lab results, and the Milken Institute’s database of treatment and vaccine trackers. It’s available to everyone—nonexclusive, royalty-free. The Farr and Eniac laws in action.

All data are constantly updated and accessible by APIs—programmable interfaces for third-party apps—which is a huge benefit to researchers, who can write simple code and start looking for patterns in the data. They can also overlay their own proprietary data to assist in, say, drug discovery.

Within days, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and others were requesting that other data be added, including chest X-rays. A large New York hospital asked for all inoculation data by U.S. county, thinking different vaccine batches might explain varying immunity. Another set of data sources goes live next week. The trick to machine learning is to correlate different elements of data and find interrelationships, things that humans can’t see. William Farr saw a curve in simple data. AI puts Farr’s work on steroids.

So here’s why C3.ai’s data lake is so important. There’s another law of artificial intelligence and machine learning: The more data, the more accurate the results will be. Alexa recognizes your voice because it was trained by millions of voices. Google pops out search results instantly because it finds patterns in exabytes of information. I actually think the value of AI goes up not by the square, as in Metcalfe’s law, but by the cube of the amount of data available. Call it More’s law? C3.ai’s Mr. Siebel predicts future uses like precision medicine, disease prediction, AI-assisted diagnoses and genome-specific medical protocols.

Patterns might be found among thousands or millions of variables. For example, anecdotal evidence suggests countries that administered the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccine to prevent tuberculosis, like Japan and South Korea, may have lower Covid infection rates. Is that true? It’d be good to know. What are the real infection rates? Does hydroxychloroquine work? Masks? Lockdowns? Anyone? Anyone?

Mr. Siebel thinks this Covid data lake may be “the most important accomplishment of the C3.ai effort” and is “confident that the probability of something good not happening from this effort approaches zero.”

Read the full article here.