- The world of artificial intelligence startups has been an amusement park of innovation and investment during the economy’s long bull run, but the roller coaster market threatens to go off its rails and crash down on the fun.

- Another obstacle for startups fighting to break through is the clamp down on data posed by regulation from Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation and other statutes.

- Acquisition or extinction are the crossroads facing many small companies, say AI exec Tom Siebel and investors in the space.

- Getting bought by a big firm with plenty of data, such as Google and Amazon, often depends on a startup’s success in a niche, such as AI’s application to fish farming.

Perhaps no area of tech has been more buzzy in recent years than the shiny sector of artificial intelligence startups. That happy innovation workshop may have just hit hard times. AI execs and investors say market volatility and regulations clamping down on data may soon lead to AI startups getting gobbled up by companies with cash and data to burn.

The market intelligence firm CB Insights said in a report this year that the 100 best-funded startups in artificial intelligence have raised over $7.4B in funding across 300 deals from 600 unique investors.

Now as the market skyrockets, then plummets in extreme volatility amid the coronavirus crisis, that may be endangered. Near the top of the heap is Tom Siebel’s Silicon Valley firm C3.ai, which builds AI programs that companies can plug into their own computer operations and is backed by some $365 million in venture capital.

A tech veteran from Oracle and then his customer relationship management firm Siebel Systems, Siebel says the heady days of AI investing are over on Northern California’s version of Hollywood’s Rodeo Drive. Gone are the days when “venture capitalists are running up and down University Avenue in Palo Alto in pink Cadillac convertibles throwing out Bitcoin on both sides of the street.”

The sector will change dramatically “when the music stops” and the market declines as it is now. “I don’t know whether it will happen this year or it’ll happen in two years, but 19 out of 20 of these companies will not exist in two years,” Siebel says. “Get acquired or go out of business,” Siebel says. “That’s just expected. I mean, that’s what will happen.”

Who’s buying AI startups?

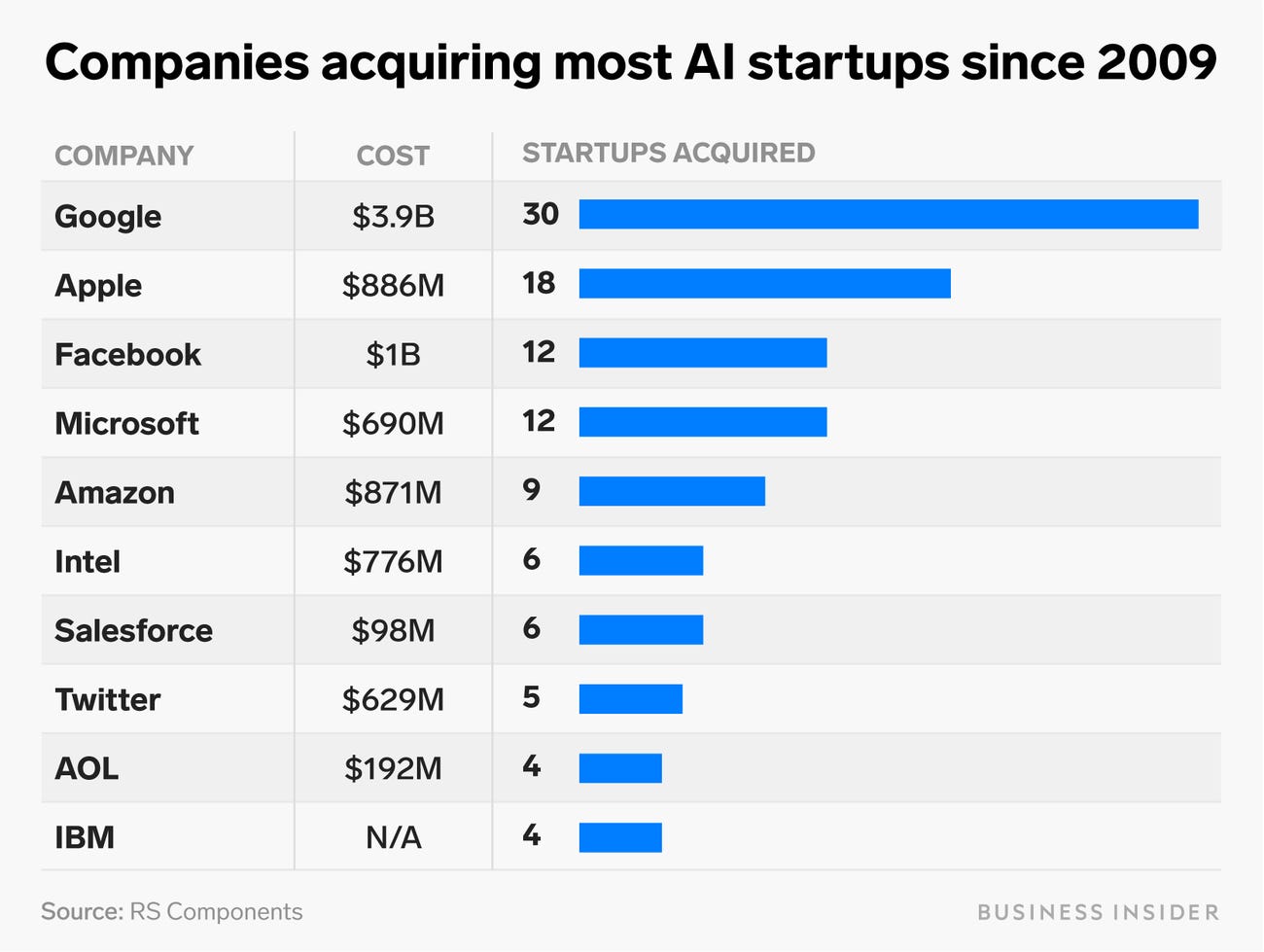

Who acquires AI startups? Very big companies with lots of money and lots of data that AI applications can work with, according to recent research by RS Components, a distributor of industrial and electronic components that conducts market research on tech companies.

This chart shows the top AI acquirers in the business:

“There are going to be a lot of acquisitions, and there should be a lot of acquisitions because there is so much noise in the market,” says Shuman Ghosemajumder, the global head of AI at F5, a Silicon Valley firm that works on application security. “The first thing I ask is, ‘How long does it take to undeploy your technology?’ Because you never know when companies will disappear.”

GDPR is putting pressure on startups

Another reason for big companies to acquire AI startups is regulation such as Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation, which has made it much harder for small companies to get consumer data, which companies like Google and Amazon already have from their users.

Data is what makes AI go. AI researchers build models – computer programs – that “learn” from huge data dumps that reflect patterns of repetition. Those patterns can be used to create algorithms, which apply the data patterns to future situations with predictive analytics. On Amazon that might look like you being presented with a product because of what you and people with similarities to you have looked at in the past.

“AI is all about data, and to have a really good solution, you need a lot of data. Regulation is making things more difficult,” says Zohar Rozenberg, vice president of Cyber Investments at Elron, an Israeli holding company that focuses on tech startups. “Startups have to find a niche solution to prove themselves, then they often get acquired.”

“There’s no way a startup could create, say, a note-taking app right now,” says John Cowgill of Costonoa Ventures, a Palo Alto VC firm that invests in AI startups. “To do that right requires too much data. Getting value out of machine learning and AI requires more customer input than startups typically have.” Data “accrues to the incumbents,” Cowgill says. The big companies keep it, and buy startups to use it.

Cowgill agrees with Rozenberg that AI startups must explore niches where they can find a pocket of data in one area. He points to one of his investments as an example.

Aquabyte is a machine learning company concentrating on one (very) small niche: Sea lice. Aquabyte scans the waters of fish farms with cameras that know how to count the tiny parasites and help farmers keep fish healthy.

“Aquabyte’s solution to a real-world problem is well on its way to transforming an industry,” says Greg Sands, founder of Costanoa. “The team at Aquabyte is demonstrating what it means to lead an industry.”

There’s something to be said for being a big fish in a very small pond. But the warm waters of AI startups may be about to get much more stormy and inhospitable.

Read the full article here.